Yesterday’s publication of the Good Childhood Report 2023 by The Children’s Society marks the twelfth in a series of annual reports about how children in the UK feel about their lives.

The majority of children and young people lead relatively happy lives. A small, but not insignificant, proportion is struggling with their overall life satisfaction, and low happiness with specific aspects of their lives.

We reflect on the report’s key findings and trends; and discuss why consistently capturing a picture of how young people feel is important for our nation’s current and future wellbeing.

Key insights and trends

The Good Childhood Report 2023 uses two data sources; The Children’s Society’s own annual household survey and the UK longitudinal survey called Understanding Society.1

Findings from the Children’s Society household survey

- Overall wellbeing – 10% of children aged 10 to 17 who completed the survey in 2023 scored below the midpoint on a multi-item measure of overall life satisfaction, suggesting that they have low wellbeing.

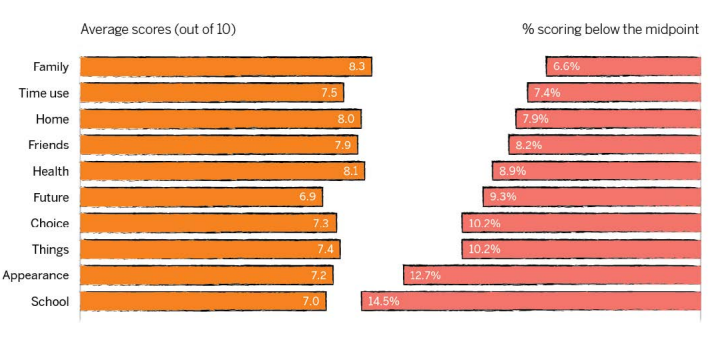

- Family, health, home – On average, children aged 10 to 17 who completed the survey this year were most happy with their family, followed by health and home.

- School and appearance – A larger proportion of those children had low happiness with school than with any other aspect of life, followed by appearance.

Latest figures from the Good Childhood Index for children (aged 10 to 17)2

Findings from Understanding Society

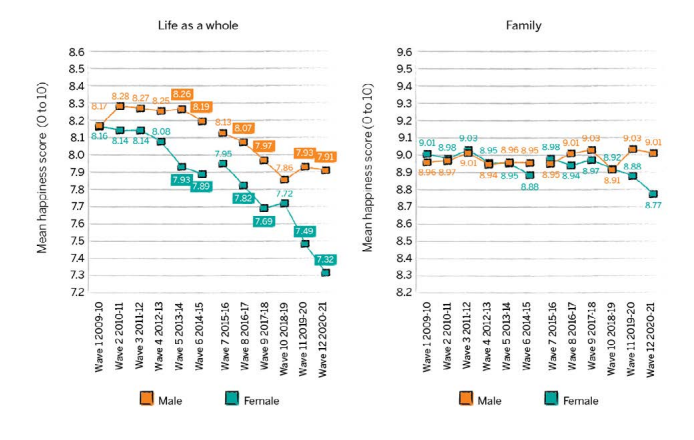

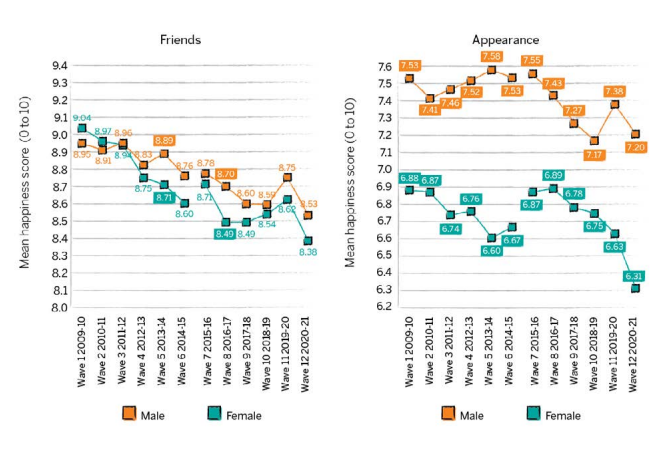

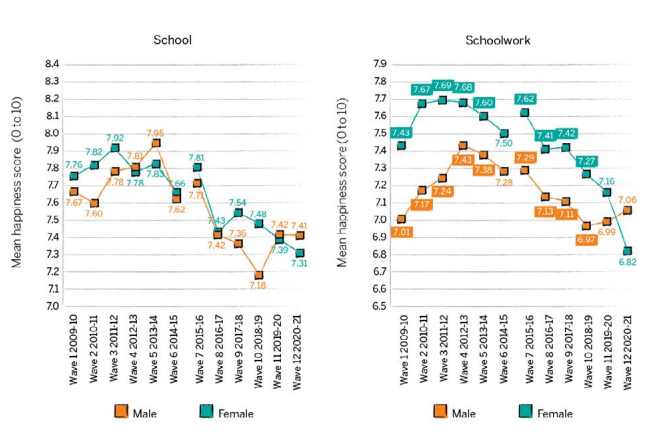

- Trends over time – The happiness of children aged 10 to 15, with life as a whole, friends, appearance, school, and schoolwork was significantly lower in 2020-21 (the latest data captured) compared to 2009-10 (when the survey began). The only exception was family, for which children’s mean happiness scores remained relatively stable.

- Gender disparities – In the 2020-21 data, females’ mean scores for happiness with their life as a whole and their appearance were significantly lower than for males.

Trends in children’s (aged 10 to 15) happiness with different aspects of life by gender, UK, 2009-10 to 2020-21.3 4

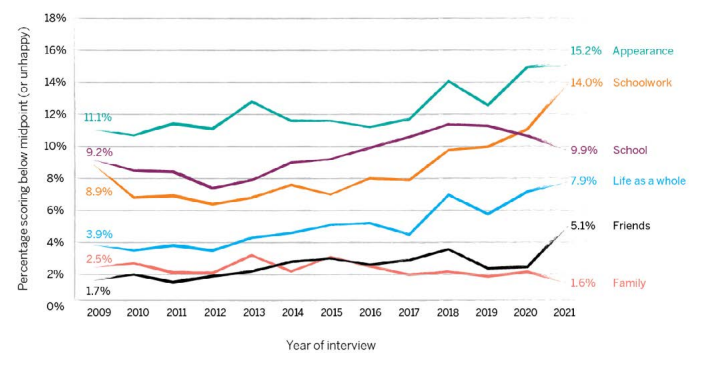

- Observations from the pandemic – In the latest two years for which data from Understanding Society are available – 2020 and 2021, which represent the two years in which there were Covid-19-related lockdowns in the UK – there was an increase in the proportion of children who were unhappy with their appearance, schoolwork, friendships, and life as a whole.

Time trends in proportion of children (aged 10 to 15) unhappy with different aspects of life, by year of interview.5

Predicting overall life happiness

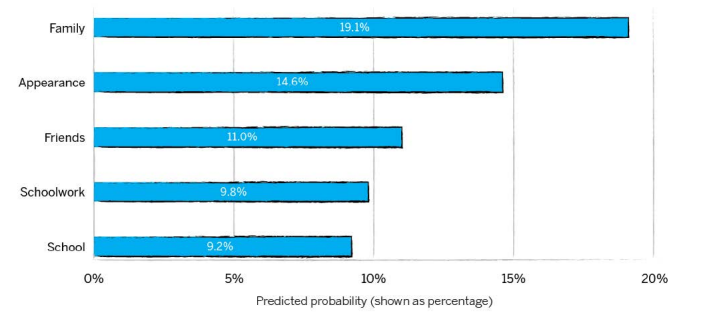

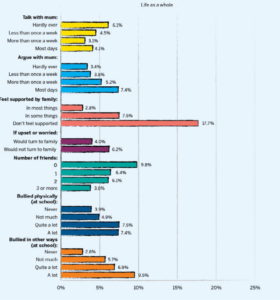

Part of the report, measured in Understanding Society, looks at whether children’s unhappiness with five different aspects of life – family, friends, appearance, school, and schoolwork – is a predictor of their low happiness with life as a whole, when controlling for other factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, and wave of the survey.

It found that approximately 31.9% of the variation in low overall subjective wellbeing was explained by the five domain measures of low wellbeing alongside demographic variables.

- Being unhappy with family, appearance, and friends was most strongly related to children’s low happiness with their lives as a whole.

- Being unhappy with schoolwork and school were less strongly associated.

- This analysis shows that children’s relationships had an important link to their wellbeing. Children who did not feel supported by their family were more than six times more likely to feel unhappy with life as a whole (17.7%), compared to children who felt supported in most things (2.8%).

Predicted probability of children (aged 10 to 15) being unhappy with their life as a whole, by relationship quality.6 7

Predicted probability of children (aged 10 to 15) being unhappy with their life as a whole, if unhappy with different aspects of life. 8 9

Hope for the future

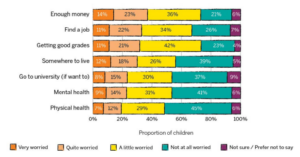

The report contains data from The Children’s Society’s 2023 household survey on the extent to which children and young people worry or feel positive about their future, including gaining employment.

The analysis shows:

- Having enough money, and being able to find a job were the top ranked worries about the future.

- A larger proportion of females than males were ‘very’ or ‘quite’ worried about getting good grades, going to university, and about their mental and physical health.

- More children aged 14 to 17, compared to younger groups, were ‘very’ or ‘quite’ worried about being able to go to university, get a job, having enough money, and having somewhere to live.

Extent of children’s (aged 10 to 17) worry about their own future 10

Children were also asked how positive they felt about their own future, the future of the country and that of the world. Most felt positive about their own future (74%) but fewer felt the same way about the future of the country (38%) and the world (36%).

Similarly, the life readiness section of the #BeeWell survey of secondary school pupils in Greater Manchester looks at the perception of future skills, careers’ education, and post-Year 11 plans.

We’ll be exploring the concept and measurement of hope further, in conversation with wellbeing expert, economist and author, Carol Graham on Wednesday 1 November, 18:00 – 19:00.

Why it matters and what’s next?

Collecting and analysing wellbeing data from children and young people over time means we can compare different generations, spot trends and track changes. This provides us with a greater understanding of what factors determine and impact wellbeing, and will help the development of safe and effective interventions. In particular it will help organisations, families and communities, who care about our young people, make the most of investment, time and effort.

#BeeWell also surveys the wellbeing of pupils consistently each year, and is now in its second year.

Measuring life satisfaction specifically is important because lower scores can predict other outcomes, including later adult life satisfaction – potentially up to eight years later.

To achieve the goal of improving wellbeing for the population, regular data collection is needed for young people, as is already happening for adults. This could be done consistently from Key Stage 2 in schools, and linked to the National Pupil Database in England or the Pupil Level Annual School Census in Wales.