From the physical state of our homes to who we share them with, where and how we live influences how we feel about our lives.

In our latest analysis, we explore English Housing Survey (EHS) data to understand the relationship between housing and subjective wellbeing in more detail, including the impact of socio-demographic factors.

The role of housing for wellbeing

The quality, location, and cost of our homes play a role in our overall wellbeing, underpinning drivers including our health, relationships, security, and the environment around us. Housing is related to social, physical, financial and human capital.

Existing evidence shows that those who live in damp-free homes or who have access to a garden report higher life satisfaction and more frequent feelings of happiness.

Negative factors in our environment, such as neighbourhood noise or vandalism, can greatly reduce our life satisfaction. This highlights that not only our home’s location matters, but also the behaviour of those within our wider community.

Analysing the data

We looked at data from the EHS Household Dataset and the Housing Stock Dataset collected between April 2013 and 2020.

We used regression analysis to investigate the relationship between subjective wellbeing and a range of factors such as age, income, and health status.

This gives us a view of how wellbeing has evolved over time and how it varies across demographic and socio-economic groups.

For details, see the full report.

Key findings

To “live in a decent house” – as defined by a home that meets 26 quality criteria – has a strong positive relationship with wellbeing. In contrast, factors such as living in substandard housing, and holding tenant status show a negative relationship with wellbeing.

The type of housing seems to play a part, with those living in terraced houses and bungalows showing higher mean levels of anxiety than those in detached houses.

Overcrowding did not appear as a significant determinant of wellbeing in the analysis. This could be because, while overcrowding is measured with an objective measure assessed by the bedroom standard, individuals may not perceive their home as overcrowded.

Renting vs. owning

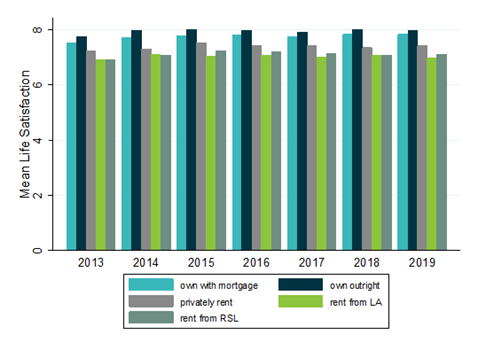

Our analysis suggests a correlation between type of tenure and wellbeing. People who own a home, even with a mortgage, reported the highest mean levels of life satisfaction, and the lowest mean level of anxiety.

Fig 1. Mean life satisfaction over time from 2013 to 2019 by type of tenure

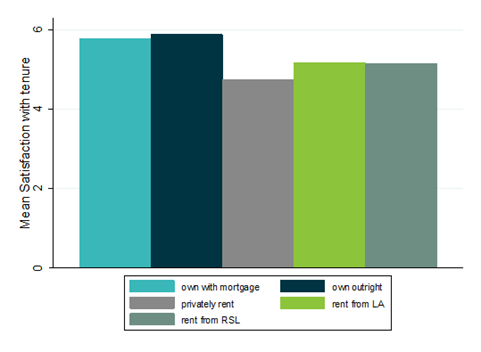

Similarly, those who self-reported being the least satisfied with their tenancy are those who are privately renting a house, while the most satisfied are those who own their homes outright, and with a mortgage.

Fig 2. Mean life satisfaction by type of tenure (averaged across 2013-2019)

The debate on whether owning or renting a home affects wellbeing presents a complex picture. Transitioning into homeownership doesn’t necessarily increase subjective wellbeing. This paradox can be attributed to the financial strains accompanying home buying, which seemingly counter the positive aspects of owning a home.

Further insights

The regression analysis showed several noteworthy associations between socio-demographic factors and wellbeing that are consistent with existing evidence. Having these measures in lots of different data sets strengthens our understanding of what impacts wellbeing. If these factors are found consistently we can have greater confidence in them.

- Age presents a U-shaped relationship with wellbeing, with young and older individuals reporting higher life satisfaction than those in mid-life.

- Gender inequalities – women report higher mean life satisfaction and also increased anxiety levels on average, in comparison to men.

- Marital status influences happiness, with married individuals reporting higher wellbeing.

- Unemployment emerges as a substantial detractor from happiness.

- Higher income levels were associated with greater life satisfaction, but the relationship wasn’t linear, indicating the effect of diminishing returns.

- Health perceptions are positively correlated with self-reported wellbeing.

Though not significantly correlated with wellbeing, damp problems are prevalent in housing, particularly in the private rented sector (7% of dwellings).

Housing is more than the four walls within which we shelter; this study highlights that while physical aspects of housing matter – and standards for decent housing should be met by local authorities and landlords – socio-demographic factors have stronger associations with wellbeing.

Using the data

Analysing datasets like the EHS can help inform public policy, identify vulnerable groups, and contribute to the broader conversation around the importance of our living environments.

Based on such insights, future policies and initiatives can be directed towards:

- Ensuring affordable housing.

- Exploring whether housing be designed and organised in a way which provides support and meaningful engagement.

- Addressing housing quality, particularly focusing on eliminating substandard living conditions.

- Observing other countries’ housing design and policies to understand if and how shared spaces and specific structures impact on the wellbeing of at-risk groups and whether there could be lessons learnt for housing in the UK.

- Investigating whether differences in renting regulations impact wellbeing.

- Reducing neighbourhood disturbances, such as noise and vandalism.

- Recognising the subjective nature of wellbeing evaluations and integrating them into larger health and socioeconomic policies.

This analysis shows how Levelling Up Mission 8, related to improving wellbeing, interacts with Mission 10 and Mission 7.

Levelling Up Mission 10 aims to provide a path to home ownership for first-time buyers and improve the standard of housing in the UK. Improving living conditions will also likely impact Levelling Up Mission 7, working preventatively to reduce health inequalities. Housing is often considered a social determinant of health – a non-medical factor that influences health outcomes.

By using data-driven insights in practice, we can work towards creating communities and homes that foster wellbeing for all.

About the English Housing Survey (EHS)

The EHS is a comprehensive annual survey commissioned by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC).

It collects information about people’s housing circumstances and the condition and energy efficiency of housing across England.

It comprises two primary components:

- interviews with around 13,300 households;

- physical inspections of approximately 6,000 households by a qualified surveyor.

The EHS datasets are publicly accessible through the UK Data Service, providing raw data for further analysis.

For further details, see the EHS guidance and methodology.

Additional resources

Explore our resources on housing:

- Housing survey analysis 2016

- Housing and wellbeing scoping review 2017

- Housing for vulnerable people systematic review, cost effectiveness model and housing first cost effectiveness assessment 2018

- Housing and Covid briefing 2021 using Covid WIRED

And our community content which includes housing:

- WEMWBS place network analysis – housing disrepair and mental wellbeing

- Individual and community wellbeing interactions

- Community wellbeing: place, people, power